A couple weeks ago I drove from my home in Central Vermont through Crawford Notch to Conway NH in the White Mountains. The mountains were beautiful and fortunately the road was clear. I managed to avoid the spring snowstorms and their accompanying avalanche warnings.

In Conway, I visited a school where I talked with students about the basics of democracy. I asked them what the alternatives were to selecting government leaders through elections. They were quick to offer monarchy and anarchy as two alternative. Given those options, I’ll choose democracy.

In the evening, I held a knitting circle at the Conway Public Library where we discussed Counting the Vote: the Process, the People, the Electoral College. One woman who attended warned me that she might start shouting when we talk about the electoral college. She says it’s the most undemocratic part of our government. She might be right.

What’s wrong with the Electoral College

In fact, the Electoral College is one of the compromises made by the Founding Fathers at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 to mollify the slave-owning states and bring them into the union. Allowing the general public to directly vote for president was just too revolutionary an idea for some of the delegates to the Convention.

The problem with the electoral college is that all the electors in each state (except two) are awarded to the presidential candidate who wins the state’s popular vote. So even if the candidate wins by a narrow margin, they capture all the state’s electors. That can result in a mismatch between the candidate who wins the popular vote of all voters in the country and the candidate who captures the most electoral college votes. That’s what happened in 2000 and 2016 when the winner of the popular vote was not elected president.

Why does this happen? Because the awarding of electors to state winners does not count the votes received by the “losing” candidate. In very large states, the “loser” in might have received a huge number of votes that could be added to others around the country to create a win in the popular vote overall.

Effect of third party candidates on presidential elections

What’s more, the presence of third party candidates can create further distortion. Since the electoral votes go to the candidate who receives the most votes in a state (a plurality), and does not require that the candidate secure more than half the votes (a majority), a third party candidate might take votes away from someone who would win in a two-person contest and leave a candidate who received support from less than half the voters as the winner.

There’s another way that third parties can wreak havoc under the rules of the Electoral College.

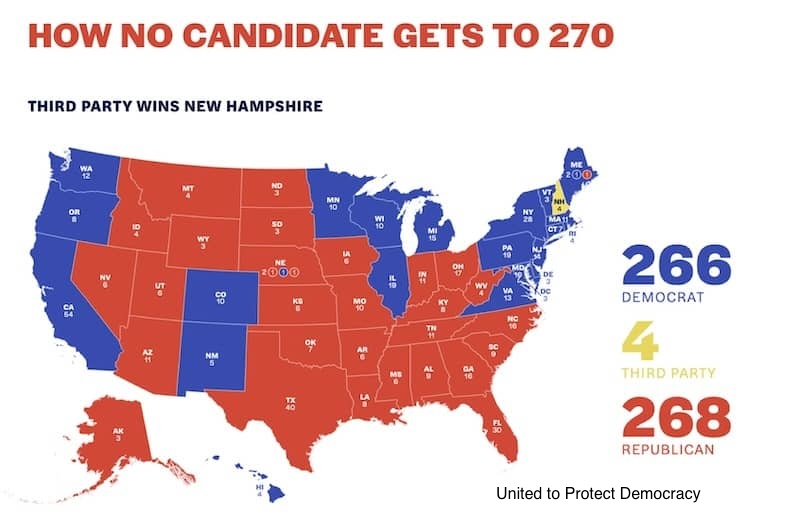

In order to win the presidency, a candidate must secure a majority of the electors. That is, they must secure at least 270 electoral votes. In our closely divided country, if a third party candidate secures even just a handful of electors by winning a small state or a district in one of the two states that awards a few electors based on congressional district, we could end up with a contingent election.

A contingent election is even more undemocratic than the electoral college. Under the Twelfth amendment to the Constitution, if no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes (270 today), then the House of Representatives chooses the president from the top three electoral vote recipients. But here’s the catch: each state gets one vote. The winner is the candidate who receives at least 26 votes. It doesn’t matter how the vote was distributed within that state or what the popular vote was in the country.

Understanding electoral college mechanics helps us vote responsibly

As Tom Stoppard said: “It’s not the voting that’s democracy: it’s the counting.”

We all need to understand the potential impact of third parties and the mechanics of the Electoral College. Navigating the rules of the Electoral College is a bit like driving through Crawford Notch. The view is beautiful, but you need to pay attention to where you’re going.

It may feel good in the moment to cast a protest vote, but in our closely divided electorate, it can have far-reaching consequences. If third party candidates secure enough votes to alter the outcome in a state or even secure a few electoral votes, we may end up ceding the power to choose the president to the House of Representative. And they won’t be bound by any obligation to select the person who won a plurality of electors or the majority of the national popular vote.